Solving suboptimal rice production in Ubon Ratchathani

UBON RATCHATHANI, THAILAND (15–16 January 2026) — A high-level workshop was convened to address the challenges of "suboptimal" rice production systems in Ubon Ratchathani, Eastern Thailand. The event was organized by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Ubon Ratchathani University (URU), and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI).

The three stakeholders, in collaboration with the Rice Department of Thailand, have engaged in a study on suboptimal rice systems to develop a roadmap for the diversification of rice production. This study is part of the Inclusive Sustainable Rice Landscapes (ISRL) project, funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and led by GIZ. IRRI provides technical support to ensure the roadmap is data-driven and informed on international good practices. The ISRL roadmap aims to transform underperforming agricultural areas into resilient, sustainable landscapes.

What constitutes suboptimal rice production in Ubon Ratchathani

The discussion among the participants highlighted that a primary driver of suboptimal yields is the unpredictable weather, leaving crops vulnerable to droughts and dry spells. These patterns have increasingly become subject to climate change. While irrigation infrastructure exists, it is often insufficient or poorly maintained, with issues such as weed blockages limiting its year-round utility.

Furthermore, optimizing nutrient application to support plant growth and grain yield would require understanding the soil composition of each farmland. However, the scarcity of soil-testing laboratories coupled with high soil testing costs prevents farmers from optimizing nutrient application in their fields. This deficiency has led to either nutrient depletion or accumulation with subsequent leaching.

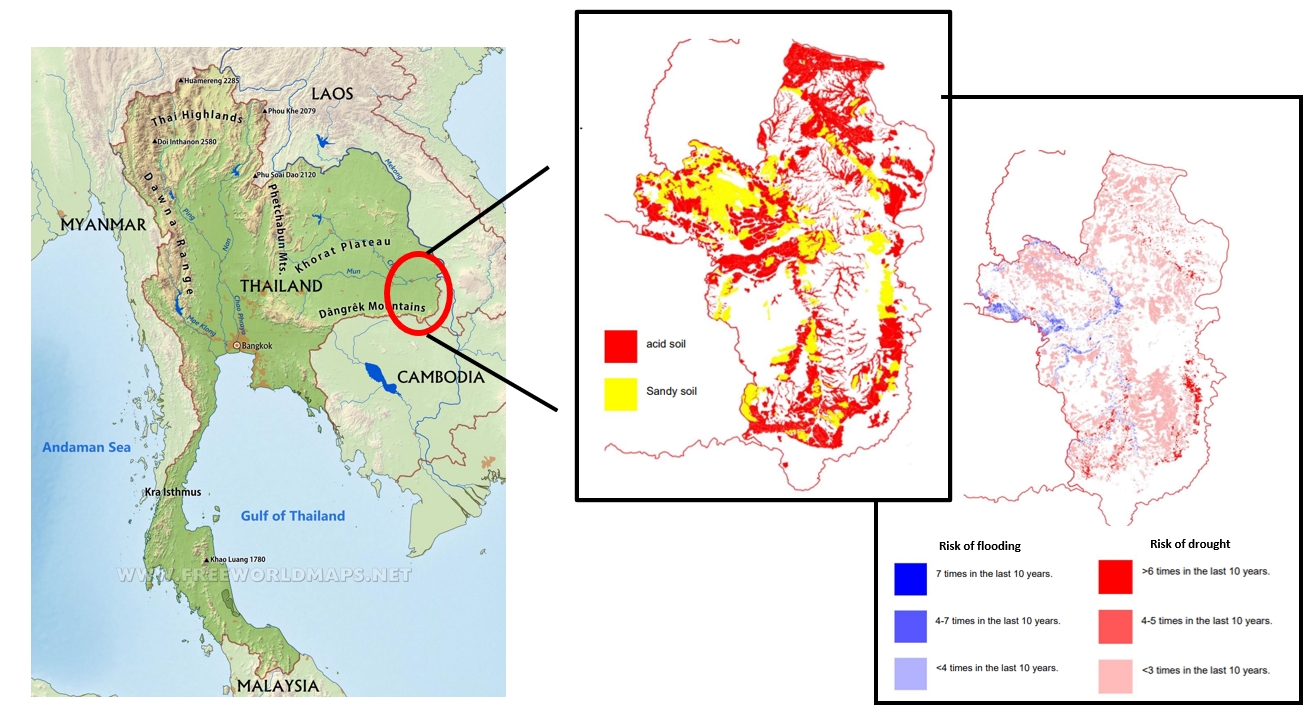

Based on Thai government data, Vorayuth Pakachaipong, Associate Scientist and Agricultural Data Analyst at IRRI, explained during a presentation that the “local soil condition is not ideal for optimal yield gains. Most of the soil is either too sandy or too acidic.”

There is a distinct "innovation gap" where traditional farming practices have remained largely unchanged for over two decades. The introduction of niche rice varieties is frequently unsuccessful, because the market remains heavily biased toward Jasmine rice. And mechanized farming, as by means of tractors, has remained inefficient if not detrimental as imported machinery turns out to be too large for local rice fields, with heavy tractors unable to maneuver under given soil conditions.

Social and economic factors also influence the optimization of rice farming, which are not limited to the northeast of Thailand. The shrinking of farmland due to inheritances passed down to farmers’ children leads to a compartmentalization of the land into smaller units. Smaller land produces lower economic returns as much as it counteracts the need for mechanized equipment. Existing farmers are either unable to generate sufficient revenue, or do not have the incentive to invest in more efficient tools. Instead, they rely on expensive external service providers lending the required equipment for farming operations.

With grain yield underperforming and available farmland being fragmented by multiplying ownerships, adjacent forest area suffers, too. Forest area is being lost at a rate of approximately 5400 rai (approx. 2,090 acres) per year. “Ubon Ratchathani ranks as the top 5 regions with forest loss in Thailand. Currently, the region has only 17.6% of forest area left; two thirds of Ubon Ratchathani land area is agriculture”, as presented by Pakachaipong.

As various meeting participants commented, the suboptimal situation is further compounded by a breakdown in the value chain. The introduction of intermediaries between farmers and millers influences purchase and sales costs, increasing production costs for farmers and decreasing revenue for millers. Moreover, the quality of rice has been impacted as control over origin and cultivation methods cannot be tracked.

Finally, regulatory support from government offices has been creating uncertainty among farmers. Initiatives tend be short lived, with financial support being cut after a few years; machinery promoted and imported to aid farming is often unsuitable for the local field requirements (as in heavy tractors); financial benefits for adopting desired rice cultivars are not clearly regulated nor communicated to farmers; and documentation requirements when engaging in government initiatives tend to be too demanding.

Finding solutions through diverse innovations and stakeholders

While several issues need to be addressed, Pakachaipong indicated that “international organizations should start by promoting better management practices” and “research on actual versus potential yield” considering the local environmental conditions. To that extent, IRRI can provide and facilitate the technical know-how via data collection on rice area assessment, such as using remote sensing technologies alongside baseline surveying.

To target improved management practices and irrigation conditions, remote sensing can be used to monitor and analyze rice production and yield. A suitable indicator for analysis is the relative growth rate. In the case of Ubon Ratchathani, Pakachaipong highlighted that “this method has shown that the areas with consistent low growth rates are the ones distant from available water bodies or irrigation systems”. These are also the areas “most at risk of droughts between three to ten times a year”, he continued.

The discussion surfaced many issues that influence the sustainability of rice production, which no one stakeholder can solve on its own. The project led by GIZ and supported by IRRI and other development partners presents an opportunity to engage with diverse stakeholders comprising rice seed centers, forest-, irrigation-, extension- and related government departments, as well as the local community consisting of farmers, millers, exporters, etc. Clearly, a single approach cannot solve the multifaceted suboptimal rice situation. A long-term approach involving every group that has a stake in rice production is needed for an inclusive and sustainable rice landscape.